Explore your options

Get a 100% confidential and complimentary business valuation.

Similar to real estate transactions, small business transactions are almost always financed with a mix of equity and debt. It’s rare for a business to sell at a strong price and for the buyer to pay entirely out-of-pocket in cash. In fact, normally we see buyers only put down 10-15% of the purchase price in cash, with the remaining amount covered by a mix of bank financing and/or seller financing (sometimes referred to as a “seller note” or “carrying paper”).

In small business sales, seller financing is involved 90% of the time. According to a recent report by the Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project, on average seller debt composes 37% of the total purchase price. The exact composition of the amount of seller financing vs. bank financing varies depending on the type of business, the risk of a smooth transition, and the size of the business. Because of these figures, at Beacon, we require all of our owners to be comfortable with seller financing at least 10% of the total purchase price.

Since most business owners have never bought or sold a business before, we often get push back from them. Homes are rarely seller-financed, so why should businesses be seller-financed?

Purchasing a Going Concern

Although the process can seem similar, there are material differences between buying a home vs. buying a business.

Businesses are typically purchased as a “going concern”, meaning the buyer is purchasing not just the equipment, but also the “living and breathing” business. This includes the name, reputation, employee base, customer lists, intellectual property, website, etc. Because of this, the buyer is willing to pay more than the fair market value of just the equipment.

When purchasing a business as a “going concern”, the buyer is valuing the business based on how much money he or she can reasonably make if they were to step into the role of the owner. Given how much small businesses typically revolve around their owners, the purchase price reflects not only how much money the current owner earns but also how easy it would be for a new owner to step in.

Allocation of Purchase Price

During the course of negotiating a purchase agreement, the buyer and seller of a small business will need to allocate the purchase price into the various assets and liabilities being acquired (e.g. what dollar is paying for what asset - tangible or intangible). Both parties will likely negotiate, as the allocation of purchase price affects the tax liabilities for each party.

For instance, if a business generates around $200K in discretionary earnings for the owner and is being acquired for a price of $550K in an asset sale, the accountants will need to determine what is being bought for $550K.

They may agree to allocate $225K to fixed assets such as furniture, fixtures and equipment (i.e. “FF&E”). They may allocate $50K to the inventory. They may allocate another $50K to the non-compete that the selling owner is signing. For the remaining $225K, it will often be allocated to goodwill. Goodwill represents the value that the selling owner has created in the business.

Types of Deals: Bank-Financed vs. Seller-Financed

Within small business deals, there are generally two types of transactions: those that are financed through bank loans (SBA or conventional) and those are financed exclusively through seller financing.

Generally, there are two instances where we see a deal being financed exclusively through seller financing.

The first is when the deal size is small (e.g. less than $200K). When a deal is that small, the costs and time associated with closing on a bank loan are too burdensome given the deal size.

The second is when the owner transition has above average risk or complexity. If there are multiple family members in the business, all of whom will need to be replaced, then the deal may be exclusively seller financed. If there are large accounts who may churn when the retiring owner leaves, then the deal may be exclusively seller financed.

The rationale here is two-fold: one, a bank may not be willing to lend to such a “risky” transaction; two, the buyer needs a lot of owner skin-in-the-game to ensure a smooth transition.

Why Do Banks Require Seller Financing?

For deals that are financed through bank loans, many owners are surprised and confused to hear that there is still seller financing in the deal terms. The reason lies in the “goodwill” that we mentioned earlier.

Unlike a house, where you’re exclusively buying a “fixed asset”, in a business transaction the buyer is purchasing a going concern and paying a considerable amount of money for the goodwill in the business.

Because goodwill is the product of customer relationships, employees, vendors, reputation, etc, there is a risk that in the course of an owner transition, the value of the goodwill drops significantly. Perhaps the retiring owner moves down to Florida and never bothers to introduce to key customers and employees. Or, all of the employees quit because of how much they love the retiring owner, leaving the buyer with no employees but a personally guaranteed loan for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The cleanest way for a bank to hedge against the owner transition is for the retiring owner to carry some of the purchase price in the form of a seller note. While the exact amount of seller financing in a bank-financed transaction varies, it typically ranges between 10 and 20% of the purchase price. Although this is typically much smaller than the bank loan, it incentivizes the seller to help the buyer come into the business and hit the ground running.

How Does Seller Financing Work?

The key terms to consider in seller financing are the amount, the term, the interest rate, and the amortization profile:

Amount: How much of the purchase price is being financed by the seller?

Term: Over what period of time will principal and interest payments be made from the buyer to the seller?

Interest rate: How much interest is due to the seller on the amount or principal being lent to the buyer?

Amortization Profile: How much money will be put towards interest and principal with each payment?

When bank financing is involved, the amount of seller financing is typically 10 - 20% of the purchase price with an interest rate of 6% and a term of 3 to 5 years. Principal and interest payments are typically paid on a monthly basis.

The amortization profile is typically 10 years with a balloon payment at the end of the term, although sometimes the buyer will also negotiate having the first year’s payments deferred so they can invest in upfront costs.

Having an amortization profile that is longer than the term means that the buyer will make smaller payments throughout the term so that they can invest more in the business, and then make a large balloon payment at the end of the term.

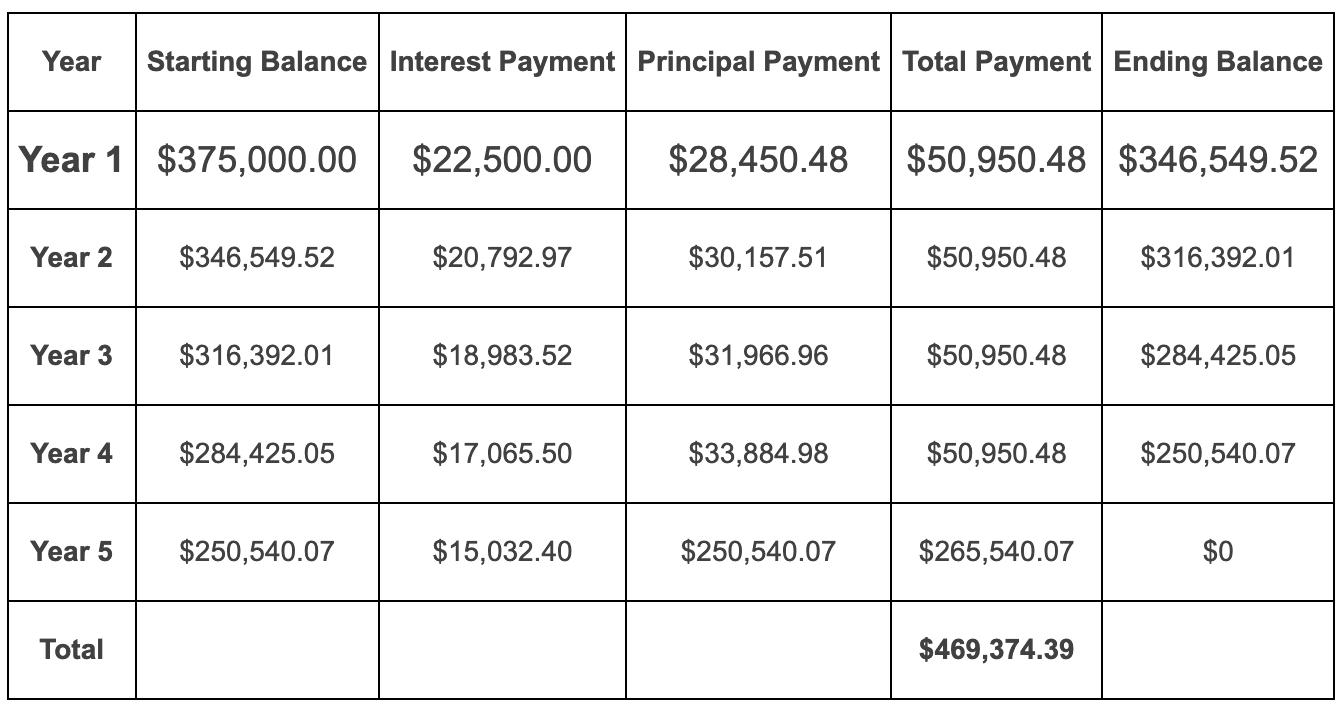

Here’s a sample amortization profile for a deal that has a 10-year amortization profile, 5 year term, 6% interest rate and a balloon payment in year 5. The purchase price was $2.5M with 15% (or $375k) seller financed.

When a deal is exclusively seller financed, the term of the seller note is typically much longer. The reason is that the seller wants to maximize the chance that he or she gets paid the amount of the note in full. If the term were too short, the debt payments would be too high and it would impact the ability of the buyer to invest back into the business to ensure success.

How to Manage Risk in Seller Financing

One common concern business owners have is that the buyer is going to run the business into the ground. Because seller financing is “junior” to bank financing, meaning in the case of bankruptcy the bank will get paid out first, they understandably want to know what they can do to maximize the chance they get paid in full.

However, owners should remember that they are normally receiving monthly interest and principal payments right after close. Few businesses fail within the first few years, so the chance that the owner collects 0% of their seller debt is very low. Nonetheless, owners should still be proactive about setting up a buyer for success.

The best way to do this is to start early. Owners who begin exit planning a few years before a sale can begin to extract themselves by putting more responsibility on key employees, which eases the transition between owners. Additionally, owners should spend time with the buyers during the pre-LOI and diligence phases. It’s a two-way street: owners should build rapport and trust with buyers, just as buyers should roll their sleeves up and understand what they’re buying.

Post-close, owners should thoughtfully consider the best way to introduce the buyer to employees, vendors and customers. There are a number of resources available online that walk through the “do’s” and “don’ts” here.

What If A Seller Does Not Want to Seller Finance?

Some owners refuse to finance any part of the deal. If this is the case, there are two options forward.

First, the owner can simply sell the fixed assets of the business. This is typically 20-30% of the value of the business as a going concern, but selling fixed assets allow the owner to move on without selling any goodwill.

Second, the owner can sell the business at a low enough price that the buyer does not need any financing at all. In other words, the value of the goodwill is low enough that the buyer can pay for it out-of-pocket.

Interested in buying a small business?

Subscribe to our Listing Alerts for early access to new listings.

Will founded Beacon with the mission to help the current generation of owners to retire while enabling the next to unleash their entrepreneurial spirit. He comes from a business background having graduated from the Wharton School with a B.S. in Economics.

Information posted on this page is not intended to be, and should not be construed as tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, investment and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.

Calder Capital

Sam Domino